The outputs of today’s climate models often sit in an uncomfortable in-between: They’re sophisticated enough to be credible in their dire predictions for our warming planet, yet their projections lack the precision necessary for businesses and governments to undertake meaningful, localized climate adaptations.

At the 2023 Climate Business & Investment Conference — a joint effort by the Tamer Center for Social Enterprise and the Columbia Climate School — dispatches from the worlds of AI development, academic research, policymaking, and various business sectors made clear that the improved climate modeling and prediction tools so desperately needed are closer than many realize.

“We need to reduce the uncertainty range,” said Pierre Gentine, professor of geophysics in the departments of Earth and Environmental Engineering and Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia. Even for simple metrics like global air temperature, he said, climate models contain significant uncertainty. “We need to try to be more precise so that we can invest better and so the cost of that investment is reduced dramatically.”

Gentine was hardly the only one to make the case for more powerful and precise climate modeling at this year’s conference — whose theme was Climate × Data” — nor was he the only one to present exciting glimpses into climate data’s future.

The day began with Gentine’s introduction to the Center for Learning the Earth with Artificial Intelligence and Physics (LEAP), a National Science Foundation-funded science and technology center founded at Columbia in 2021. Gentine also offered a demo of LEAP Pangeo, an aggregation of some of the powerful climate modeling tools the center is developing.

Gentine, director of LEAP, explained that as a cloud-based data and computing platform, LEAP Pangeo is “a simplified way for anyone with a laptop and an internet connection to access the type of climate data they need to move toward effective climate adaptation.” Public access and usability, he added, are key to the mandate of LEAP. “We see that as a critical point that’s been missing in the past: providing climate data at scale to the broader community.”

Andrew MacFarlane, head of climate at global insurer AXA XL, echoed Gentine’s point, emphasizing that his industry sorely needs better tools to digest and understand the 2,500,000,000,000,000,000 bytes of climate data collected every day.

“When it comes to climate data, although we’re collecting large volumes, I would have to say the quality and the availability for what we need is still poor,” MacFarlane said. “Improving the resolution, using tools like [LEAP Pangeo], really will help us to understand the risks that we take on as the climate evolves.”

Over the course of the conference, other common themes emerged from panel discussions and interactive presentations, converging around five key takeaways:

1. The right answers for the climate can be counterintuitive.

“Here’s a question: Do people really know how to turn their concern [about climate change] into action?” asked Eric Johnson, professor of business at Columbia Business School, during his interactive demonstration of his recent research. “I’m going to argue there are reasons to suspect they don’t.”

Johnson presented the audience with a pop quiz to complete on their phones, posing a deceptively simple question: If you were to advise the average American on how to reduce their annual carbon emissions by half, what would you suggest they do? When the options presented are reducing waste by 25 percent, halving their meat consumption, taking one fewer round-trip flight, reducing their home electricity usage by 75 percent, living car free, and purchasing carbon offsets equal to half of their emissions (ordered here from least to most impactful — “and we’re believing offsets work here,” Johnson added as a caveat), most Americans “don’t have much of a clue,” Johnson’s research has revealed.

“One big belief in most discussions of climate change is that those consumers who want to change things will,” Johnson explained. “What we’ve been doing [in this research] is actually trying to understand, what do people actually know about their behaviors?”

Given that their understanding of which personal actions yield the greatest emissions savings is so murky, Johnson suggests that steps like better labeling disclosure on consumer goods and plane tickets, for example, could lead to cleaner choices.

But a misunderstanding of how we impact the climate — and how the climate will impact us — isn’t limited to the average American. Hamid Samandari, senior partner at McKinsey, noted that even experts working hard to grok climate change’s future impacts on their businesses struggle to do so without data modeling of next-level sophistication.

He presented the case of an electric utility client in the Great Lakes region that enlisted McKinsey to help it understand its climate risk exposures over the next decade and the impacts on its electricity load. Modeling it out, the McKinsey team realized that because of the increased use of heat pumps, the load for the utility was actually likely to increase in the winters, not in the summers — even as temperatures rise.

“It’s very interesting how certain things are unintuitive,” Samandari said. “This is a theme in climate in general: Quite often, second-order effects can either negate or vastly amplify first-order [ones].”

What tools might be useful in incentivizing the narrowing of the gap between climate understanding and reality? What new incentives can be created to help consumers and private-sector actors actually understand the problem and then act in the most beneficial ways? Two Columbia professors tested one possible tool, based on predictive markets.

Moran Cerf, faculty of Executive Education at CBS, and Sandra Matz, associate professor of business at the School, presented the key results of their new study (funded by the Tamer Center for Social Enterprise), which tests the effectiveness of climate prediction markets in boosting support, concern, and knowledge around climate action.

First, they sent online surveys to roughly 700 participants to measure baseline attitudes about climate change. Next, half of the participants were assigned to the intervention: a climate prediction market. Every day for four weeks, the researchers sent this group a climate “bet” — for example, whether temperatures would rise to a certain level — and participants read up on subjects related to the bet, then decided whether to accept and with how much money to bet (up to $1).

Cerf and Matz found an uptick in concern, support, and knowledge among the participants who had taken part in the prediction market intervention. The results held across the political spectrum.

“Today, holding false beliefs about climate change doesn’t really come at a cost,” said Matz. “The idea was, if we can integrate this into a market, suddenly, continuing to hold these false beliefs comes at a cost.”

2. It’s crucial to look past averages and start focusing on climate extremes.

“Importantly, global temperature is not changing everywhere the same way,” said Gentine, who added that LEAP Pangeo helps to crystalize the ways in which this is true. “It’s actually affecting the land regions much more — there's almost double the amount of warming over land than over the ocean. So we are experiencing climate change a lot more than what we're actually seeing at the global scale.”

Gentine added that warming also varies significantly across regions; it’s having more impact, for example, over the Amazon.

Samandari underlined this point, noting that McKinsey’s climate modeling was revealing the same. When the firm produced a map of future storm-driven outages for its electric utility client, it found that while the average outage hazard increased in its projections to roughly 15 percent (from almost no risk today), some regions faced an outage hazard of 30 percent.

“You hear people talk about averages, but climate is really about all the parts of the distribution — particularly the extremes,” Samandari said. “And if you want to take action, you need to understand that distribution and those extremes.”

3. AI is radically transforming climate modeling capabilities.

“Already, AI-based weather prediction is completely disrupting the business of predicting the medium-range weather,” said Mike Pritchard, professor at the University of California, Irvine, and director of climate simulation research at NVIDIA, a supplier of supercomputers and other types of artificial intelligence hardware and software. Pritchard said that, once trained, NVIDIA’s weather forecasting model can predict two weeks of weather in a quarter of a second — 10,000 times faster than classical weather implications. “The science of studying these likelihood extremes stands to benefit from AI methods of predicting weather,” he said.

But AI’s prediction possibilities extend much further, of course. Pritchard suggested that “digital twins” of existing libraries of climate predictions could act as a back end for the sorts of visualization tools that LEAP and others are developing.

“There’s a vision out there for the world to try to self-assemble networks of digital twins that can allow us this paradigm shift — to see our agency, for businesses to understand their agency and see how decarbonization in North America actually interacts with the hazards of the future,” he said. NVIDIA’s Earth-2 initiative seeks to make this vision a reality, he added.

LEAP’s Gentine explained that on its own, AI is not great at extrapolating new patterns. Even ChatGPT, he noted, learns from patterns it has seen. Physics, on the other hand, allows you to extrapolate beyond what’s familiar.

“What we are trying to do is actually bridge AI and physics,” Gentine said. “You can actually provide much better projections of the future by bridging those two.” He explained that this is how “LEAP will really take a leap in climate projections.”

Uses for AI don’t stop with climate modeling and prediction, however. Melanie Nakagawa, chief sustainability officer at Microsoft, noted that lesser discussed AI use cases could be in accelerating the discovery of low-carbon materials. Collectively, common industrial materials like cement, steel, and plastics contribute about 20 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions, she said, and while lower carbon alternatives exist, they’re usually costly and difficult to develop at scale.

“But now, with this new era we’re in with AI, there are infinite combinations that could be explored through materials research,” Nakagawa said. “AI can help tackle this faster — accelerating materials selections and prediction of its properties and reducing the design and validation process of new materials from decades to years or sooner.”

4. We can’t forget the importance of ensuring the quality of the underlying data.

“Even though we all like to talk about the most sophisticated, forward-looking models that everyone's working on, I actually want to bring everyone back to the basics,” said Linda-Eling Lee, head of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) and climate research at MSCI. “I want to talk about company emissions, because that is such a primary input into the hundreds of climate metrics that are used by investors today and in the financial world.”

In her role at MSCI, Lee has helped build the world’s largest provider of ESG ratings and models to the investment industry. These ratings, and other climate metrics used by investors, researchers, and capital allocators operating with a climate lens, typically rest on a foundational layer of company emissions data. However, she noted, despite a recent uptick in companies reporting on their emissions, only one-third of publicly listed companies report their scope 1 and scope 2 emissions — the rest have to be estimated. Lee fears that too few actors relying on such data understand the quality questions they ought to be asking.

“The key message to all of you is that you should question the quality of emissions data,” Lee said. “Any emissions data that you're using, you really should be asking: Where did that come from, and was it well validated?”

5. Governments have a critical role to play in making the data matter — by putting a price on carbon.

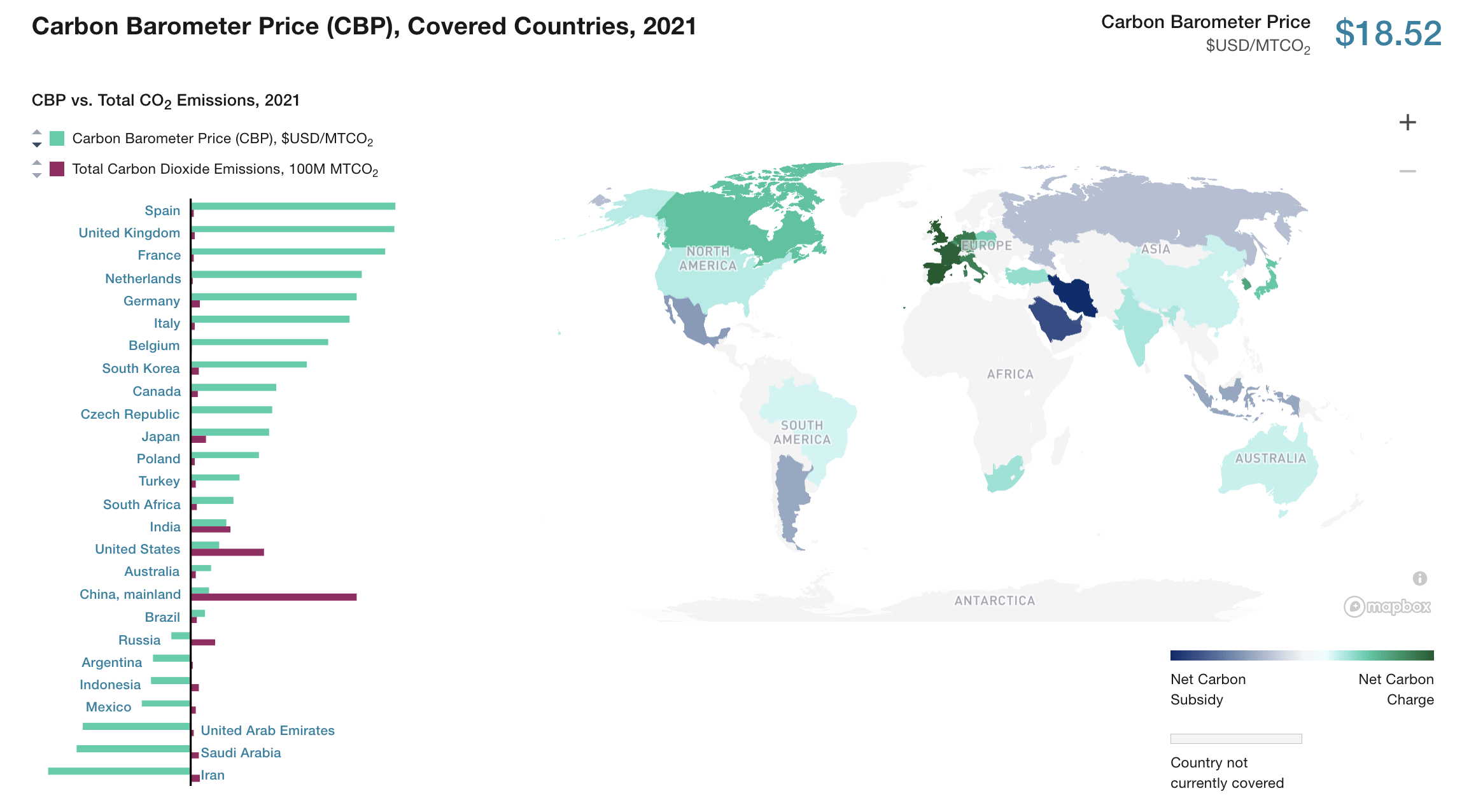

“Incentives are so important to change behavior,” said Bob Litterman, a founding partner at Kepos Capital and chairman of its risk committee. He shared a graphic that summarized the incentives around the world to reduce (or keep emitting) carbon, called the Carbon Barometer (see below).

“The main picture you see is that the global average price on carbon is much too low, at $18.50,” Litterman said. He noted that the policies incorporated into the graphic aren’t just explicit carbon-trading regimes but also, for example, fossil fuel taxes (which is where most of the incentive to reduce emissions in the United States comes from — even though the taxes were not imposed for that reason).

What to do about this lack of present-day policy to motivate change?

“One idea is to create a forward-looking measure of what incentives are going to be in the future,” Litterman said. “If you think about what's going to incent those $3 trillion to $4 trillion of investments that we need to reduce emissions and suck CO2 out of the atmosphere, we need to expect that in the future, there's going to be an incentive. Capital flows where it expects to make profits.”

Click here to watch recordings of each of the sessions at this year’s climate conference (hyperlinked on the event page for each session).