Will we soon be seeing robots on sidewalks delivering groceries—or even scanning the streets to enforce stay-at-home orders? Once relegated to the realm of science fiction, human-facing robots may soon become more commonplace, thanks to their now in-demand potential to do routine tasks without spreading the novel coronavirus.

“This pandemic has created an interesting new landscape for thinking about advancements in consumer-facing robotics,” says Bernd Schmitt, the Robert D. Calkins Professor of International Business and Faculty Director of the Center on Global Brand Leadership at Columbia Business School. “Not only has the pandemic created many new immediate uses for robots, but I predict it will also change consumers’ perceptions of service robots from one of relative skepticism to acceptance, and more quickly than we previously expected.”

Professor Schmitt has researched consumers’ perceptions of service robots for years in anticipation of their future importance to businesses, and he sees in the pandemic a turning point for adoption of service robots in areas like healthcare, food delivery, and public safety.

As new social norms take hold, how might robots be employed in consumer-facing roles? What roadblocks still lie ahead for their adoption? And what design considerations should businesses have if they are considering adding robots to their business strategy?

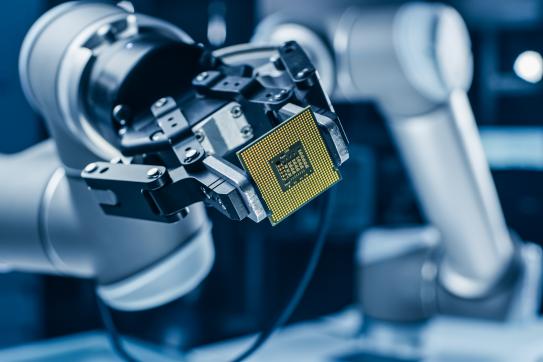

Although robots have been used in industrial settings such as automotive plants since the 1960s, physical consumer-facing robots are currently a rarity in Western countries—but they may now be able to help us in places where humans are at high risk for being infected, like hospitals. Some hospitals in China, for instance, have been using robots from Danish company UVD Robots to autonomously disinfect hospital rooms with powerful ultraviolet light. Austin-based Diligent Robotics makes a friendly-looking robot named Moxi who autonomously restocks hospital rooms with supplies and does other routine tasks. Mountain View-based Nuro specializes in self-driving delivery vehicles, which have recently been used to move food and medical supplies around a California stadium that is serving as a temporary coronavirus treatment facility. Some future possibilities for robots in healthcare include performing coronavirus testing and being used for social companionship for hospital patients.

Beyond healthcare, there are many more use cases for using robots to limit human-to-human contact. In Tunisia, for example, security bots with thermal devices patrol the streets of the capital to enforce a strict lockdown. Startups such as Kiwibot and Starship Technologies have developed robots that can deliver groceries and supplies around small communities such as college campuses. (It’s also worth noting that the pandemic has only hastened the adoption of a related technology—voice-activated home appliances and devices with AI assistants such as Amazon Alexa—which allow consumers to avoid touching surfaces.)

While the needs caused by the coronavirus pandemic might seem like a boon to companies that make consumer-facing robots, the timing may be just short of ideal. Many roadblocks to adoption still remain, including the difficulty of suddenly ramping up production of the robots ahead of government approvals on where and how robots can be deployed. Additional considerations such as infrastructure (the non-robot components such as logistics, app, and support) also need refinement, and currently, the robots are only able to deliver over short distances.

What has not been widely explored yet is that in addition to the technical roadblocks to adoption, powerful emerging technologies like consumer-facing robots must also pass the proverbial smell test with humans before they can enjoy widespread popularity. In order to make robots that will be accepted by consumers, Professor Schmitt has a few design recommendations. “When we have a consumer-facing robot, we have different visual design needs from if we were making a factory robot, because we have the additional requirement of being trusted and accepted by humans,” Schmitt says. “There is a reason why the robots that have had commercial success with humans so far—for example, SoftBank’s Pepper—tend to have a cute, toy-like, benign appearance.”

Schmitt studies what is known as the “Uncanny Valley,” or the level of anthropomorphism in a robot at which a human viewer starts to feel uneasy about the resemblance. “A less anthropomorphic robot like Pepper is seen as a benevolent helper, while on the other end of the scale, a perfectly humanoid robot is perceived as, well, creepy.” Because perceived warmth is important to consumer acceptance of robots, Schmitt recommends that organizations that might use robots as frontline workers in the future, like restaurants and grocery stores, consider a less anthropomorphized appearance for their robots. “But this pandemic has changed everything,” Schmitt adds. “We may see consumers trusting robots a lot more quickly, regardless of the physical appearance of the robot, now that robots could be seen as literal lifesavers.”

But while robots could keep humans more safe from harmful viruses, there still is no unified answer on how to generate income for the millions of humans whose jobs they would replace. That is still a question that is being tackled by experts in everything from philosophy to public policy to technology, and worried about by people of all economic stripes. Professor Schmitt prefers to see the glass as half full. “In an ideal future, working robots would not replace humans, but would instead free humans up to do the creative, strategic, relational work that they are best suited to do.”